Given the growing prevalence of obesity, it is tempting to think of food as a barrier, but it is actually key to improving health. Eating a balanced diet based on whole, nutritious foods can complement conventional treatments for certain diseases, and in some cases, prove preventative.

Nutrients are the crucial elements in food, being essential for the growth, development, and maintenance of core body functions. In the absence of certain nutrients, our health can decline. Because nutrients provide our bodies instructions about how to optimally function, food serves as a key source of “information” for the mind and body. Better nutrition is often the most cost-effective, noninvasive intervention to prevent or limit a progression into disease; good nutrition is good medicine.

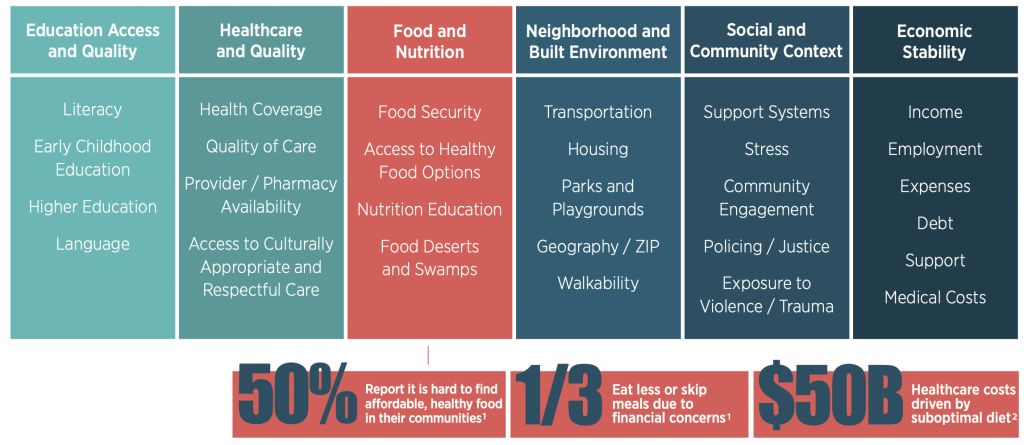

Food acts as medicine to prevent and treat disease, so what we eat is absolutely central to our health. As noted, the food we consume gives our bodies the information and materials they require to function in a healthy, proper way. In the absence of this data, our health can decline (e.g., metabolic processes can suffer). The COVID-19 pandemic has further compelled us to re-examine food and health systems, making this an opportune time to explore new ideas and to develop creative partnerships addressing suboptimal diets and widespread nutrition inequities, such as inner city and isolated rural food deserts. For example, the potential contributing role of vitamin D deficiency in COVID-19 mortality2,3 caused increased attention to the crucial role of well-balanced nutrition for attaining and maintaining health.1,2 All these factors have come together to drive a new social movement focused on the interconnectedness of food, health, nutrition, and social determinants of health (SDoH).

The food-as-medicine movement involves cultural, economic, medical, political, and social factors. It sweeps in business leaders, community leaders, healthcare professionals, policy makers, and other key stakeholders. There is a growing body of research linking food as a formal component of patient care and treatment. Because of the global epidemic of diet-related diseases such as diabetes, there is a substantial increase in utilization of food-as-medicine interventions to prevent, manage, or reverse illness. These interventions include medically tailored groceries, produce prescription programs, and medically tailored meals. We actually prefer the term Food For Health because our approach addresses clinical nutritional needs, as well as the role food plays in our overall physical and mental well-being.

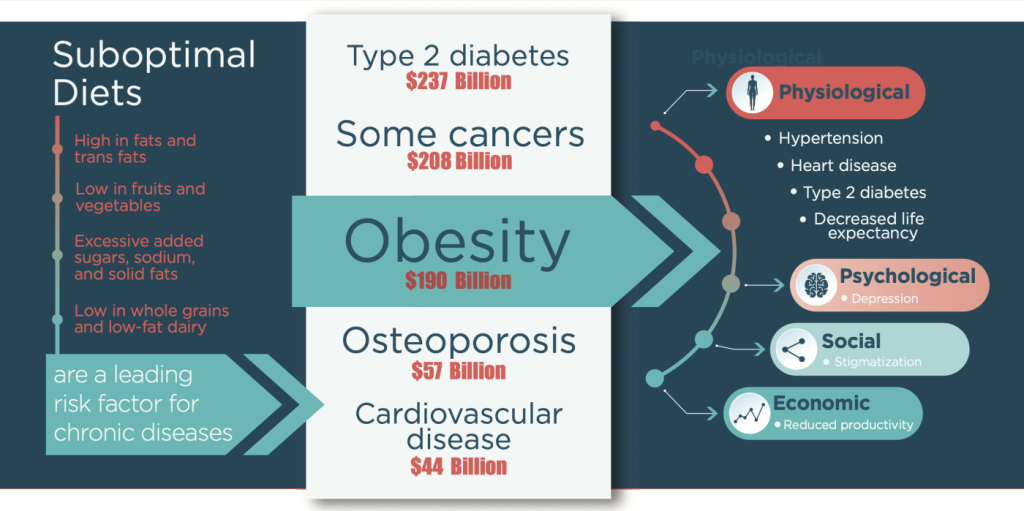

Conditions and diseases directly linked to being overweight include arthritis, diabetes, and heart disease. In fact, 78% of healthcare expenditures are for treatment of chronic disease. Stroke and certain cancers are related to obesity and poor nutrition. Moreover, we have known for at least three decades that about 80% of all chronic disease and premature death globally is preventable by a mix of healthy eating, routine physical activity, and avoiding smoking. Poor nutrition alone accounts for 11 million deaths globally, including from causes such as cancer, cardiovascular disease, and type 2 diabetes.

The development of cardiovascular disease is driven by multiple factors, including elevated cholesterol, excessive homocysteine, heavy metal toxicity, hypertension, inflammation, insulin resistance, oxidative stress, and overall stress. The key observation is that each of these factors can in turn be influenced by nutrition. A deficiency in mineral balance can be an important contributing factor to the development of congestive heart failure. Being overweight is also a risk factor for initial and recurrent breast cancer. According to researcher Ashkan Afshin, MD, MPH, MSc, ScD, professor of global health at the University of Washington’s Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation in Seattle, “Low intake of healthy foods such as nuts, vegetables, whole grains, and fruits, combined with higher intake of unhealthy dietary components such as salt and trans-fat, is a major contributor to deaths from cardiovascular disease in the United States.” Thus, a food-for-health strategy has direct implications for lowering mortality and improving the quality of living.

Healthy eating allows us to feel good, have energy, and maintain health. When combined with being physically active, healthy eating is a highly effective way of maintaining a healthy weight, and what we eat can affect our immune system.

For decades, we have seen a growing volume of high quality peer-reviewed, scientific research establishing this clear link between poor nutrition and poor health outcomes, especially with regard to chronic illnesses such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and hypertension.

Illness can arise from not only insufficiencies of food but also excesses of unhealthy foods that can drive obesity and co-morbidities. For example, 80% of the immune system is contained in the gastrointestinal system, and a meta-analysis on the impact of low-carb diets on heart disease indicated a significant beneficial effect on reducing cardiovascular risk factors. To examine the full role of food, we must consider the interconnectedness of the detoxification system, the digestive system, and the immune system.

Because of the significant impact of COVID-19 on mental and physical well-being for billions worldwide, there is an enhanced interest in eating foods serving health-related purposes. Consumers, particularly young adults 18-24, are becoming increasingly aware that their food choices can help prevent, manage, and even reverse certain medical conditions. Some diet plans have been shown to prevent many chronic diseases, including cardiovascular disease. Food and nutrition even hold the potential to help achieve reversal of disease, as in the case of type 2 diabetes. One key study shows that a 7% loss of weight (attained via exercise and a low-fat diet) can help individuals with prediabetes reduce the rate of developing type 2 diabetes by 34%.

Dietary changes can improve the course of treatment for diseases such as cancer, chronic kidney disease, Crohn’s disease, diabetes, and ulcerative colitis. One study involving over 1,000 patients, showed that medically tailored meals produced a 16% reduction in total healthcare costs, nearly 50% fewer inpatient hospital admissions, and over 70% fewer skilled nursing facility admissions. Another research study showed that elderly patients discharged from the hospitals who received Meals on Wheels food delivered to their homes experienced substantially lower hospital readmission rates.

The proper “mind diet” of certain foods may even help in preventing Alzheimer’s disease, the most prevalent type of dementia. Studies indicate that consumption of a Mediterranean diet is correlated with slower rates of cognitive decline in elderly adults. Plant-based meals have been linked to lower risk of depression and decreased mental function, as well as reduced chronic diseases.

There is a direct connection between the food-for-health perspective and the concept of public health (i.e., community and population health). One in five deaths globally is attributable to a poor diet, more than any other causal factor including tobacco. The elements of a poor diet include excessive sodium, red or processed meat, and sugar-sweetened beverages, as well as insufficient quantities of beans, fruits, lentils, nuts/seeds, polyunsaturated fats, seafood-based omega-3 fatty acids, and vegetables. This population-level impact of poor food choices is particularly striking in the U.S. Assessed along many criteria, the U.S. population is the unhealthiest (e.g., higher rates of chronic disease, lower life expectancy) of any high-income country, even though it spends more money on healthcare as a percentage of the economy. Over 40% of American adults and nearly 20% of children under 19 years old are obese. The U.S. has the world’s 12th highest rate of obesity, right after Kuwait and 10 small Pacific Island nations.

However, in order for the food-for-health concept to be impactful, communication and education are required. Every effective nutrition intervention discussion can serve as a teaching moment for patients, providers, and the public. When deployed on a widespread basis, diet/food interventions that work for individual consumers and patients hold potential to positively affect community-wide wellness and population health. Many food-as-medicine interventions can be integrated into business incentives, consumer education, healthcare delivery, strengthened federal nutrition assistance programs, and regulatory/labeling policy.

There is a connection of all this to food justice. One could argue that access to healthy, nutritious food is so fundamental as to be more than medicine. Access to nutritious foods should not be a luxury afforded to few. In the U.S. alone, over 900 deaths per day are related to poor diet via heart disease, stroke, and type 2 diabetes. Those most likely to die due to poor diet are Black or Hispanic, young, relatively less educated, and relatively low-income. One key reason why communities of color suffer is due to “food deserts.” These are generally defined as areas without a full grocery store within a mile of a person’s home. Instead, there is often ready availability of cheap, convenient, unhealthy food — defined as “food swamps.” These disparities often result in quantity over quality of foods, if quality is even an option. Thus, food for health is also food for justice.

The food-for-health movement is upon us, and it holds significant potential to improve healthcare quality, cost, and access. Persistence of food deserts and swamps, prevalence of chronic conditions, and rising costs of healthcare are social, environmental, and economic issues we can impact through access to nutritious, wholesome foods. Approximately 6 in 10 adults in the U.S. are living with a chronic disease, and 4 in 10 adults are living with multiple chronic conditions. The economic impact alone is enormous. Healthcare expenditures in the U.S. are approaching the $4 trillion mark with forecasts for significant increases in spending over the next decade from the aging baby boomer population alone. Solutions such as Food For Health medically tailored grocery delivery and other food-as-medicine programs are an opportunity to have a significant economic impact and drive better health for all.

Chief Health Officer, Umoja Food For Health

Senior Advisor and Strategy Consultant, Stanford University School of Medicine

Research Affiliate, Yale University School of Medicine

Co-Founder and Board Member, Black Healthcare and Medical Association

Advisory Board Member, Healthcare Businesswomen’s Association

Northwestern University Kellogg School of Management, M.S., Ph.D.

Harvard University School of Law, J.D.

Princeton University School of Public Policy, M.P.A.

Massachusetts Institute of Technology, B.S.

Carnegie Mellon University Heinz School; Rand Graduate School

Senior Advisor, Umoja Food For Health

Early Career Professional Presentation Award, American Psychological Association

Most Promising New Textbook Award, National Winner, Text and Academic Authors Association

Best-selling book on SAGE list for general statistics market

Published more than a dozen books in statistics, methodology, strategic analytics, behavioral health, and healthcare

More than 200 institutions have adopted his books, including Columbia, Darthmouth, Harvard, Johns Hopkins, and Stanford

Quoted in The Wall Street Journal, The Huffington Post, Time Magazine, and Oprah’s Magazine

Board of Directors, Olean General Hospital Foundation, and the Center for Women in Healthcare and Life Sciences

Arizona State University, Postdoctoral Associate

University of New York at Buffalo, Ph.D. in Behavioral Neuroscience and Psychology, M.A., B.A.